The Art of “American Splendor, The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar

The Style of American Splendour

A Personal Introduction to the Artists of Pekar’s “American Splendour”.

The “American Splendour” series by Harvey Pekar is well known for its unique and divergent art as the author was not an illustrator and needed to hire others for the drawing component. He spent much of his early career as an indie comic creator struggling to find local Cleveland artists to work for whatever small sums he couldpay them to draw for him. In turn, he ended up establishing long term connections with a many of these illustrators and used their skill throughout the duration of the “American Splendour” franchise. His most famous collaborator was Robert Crumb, but he also worked with Greg Budgett, Gary Dumm, Gerry Shamray, Susan Cavey in addition to many others. Each artist brought their own touch and perspective to the series, making it a unique hodgepodge of artistic style and substance.

The range is rather expansive, from the graphic style of Greg Budgett to the symbolist approach of Susan Cavey. In a way, Pekar’s lack of overt visual artistic skill benefited his work greatly in the same way that two heads are better than one. Through the minds eye of his artistic companions, different aspects and angles on how Pekar communicates with the reader or how emotional quantities are handled come forth.

Most of his collaborators, especially Crumb, really liked to break the fourth wall by having Pekar’s in-comic character address the readers directly. On the other hand, Shamray and Cavey did so much less and preferred a more introspective Pekar. Either approach has its own merits. Having Pekar address the reader directly pulls them in and makes them feel like they are having a personal conversation with the panels as they read. The reader becomes an additional character and is invested in the life of Pekar as one is to a close friend.

The introspective approach transforms the reader into a voyeur. The book becomes a door; we peek through the keyhole to catch a glimpse at what is going on. Instead of being pulled into Pekar’s personal space like in first person, we are pulled into his world instead. This feels more immersive in terms of place and time, but less interactive.

While Shamray and Cavey may have introspection in common, the way they render their images are different. Shamray used photo reference while Cavey mostly used her imagination with the odd photo reference on occasion. Shamray’s renderings are plotted and anchored to their environments while Cavey’s depend on symbols and the suggestion of form. Budgett and Dumm, on the other hand, often collaborated together with one as penciler and the other on inks. Budgett’s work is more graphic and depends on environmental placement amongst almost technical like drawings while Dumm illustrates a much more liberated world of messy lines and angles.

Special mention must go to Crumb as he was an important artistic influence on the illustration scene throughout the late 60’s and into the 70’s. He managed to give a visual voice to the raw and gruff words of Pekar that a traditional superhero style would not have. There is something poetic about these two free spirits finding each other and collaborating on “American Splendour”. Both have a history of doing things their own way with a general distaste for the mainstream aesthetic.

It must be said that each artist that Pekar worked with must have enjoyed his company on some level because as one reads, image and word merge effortlessly into one. There is something strange about the magnetism of Pekar’s words that transforms and slightly alters each artist’s work. It is an experience that must be had in person and is difficult to explain. The series is the sum of its body parts, with Pekar’s prose being the crown on top. Needless to say, it would not have been what it is today without the contribution of his artists, especially in those early days of the late 70’s and early 80’s. For that, I as well as many others am very grateful for their contribution to this milestone in graphic memoirs.

Brian Bork

Robert Crumb

Official website here.

Introduction

Arguably, the single most iconic and well known artist to work with Pekar was Robert Crumb, an underground artist most famous for his commentary on mainstream American culture during the late 60’s, 70’s and beyond. Their first collaboration occurred in 1976 which also happened to be the first issue of American Splendor. Pekar and Crumb continued to work together for years after and became good friends.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

As a graphic memoir, Crumb chose to illustrate Pekar’s prose half as Pekar speaking directly to the reader and half through flashbacks. The fourth wall was constantly broken when Pekar’s illustrated alter ego would address the reading audience directly. Crumb, compared to any other artists chosen for “The Life And Times of Harvey Pekar”, used this style of third person/first person narration the most. It both engages the audience and increases the sense of intimacy that they share with Pekar. In turn, the flashback sequences ground the story with prompts for important moments in the narration.

Perhaps a less flattering interpretation of this stylistic approach was that Crumb was simply trying to cut costs. The third/first person narrative approach could have been a way for Crumb to reduce his production costs by not spending time worrying about environments and other additional visual information that would have taken extra time. His panels depicting Pekar speaking to the audience are bare of additional visual information beyond Pekar’s figure.

Nuance of Expression

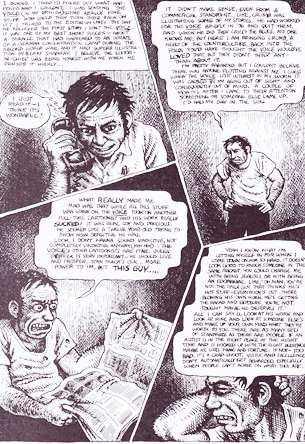

Whatever the reason for Crumb’s use of Pekar as narrator, he was able to showcase one of his best skills as a visual storyteller: his sense of nuance within emotional expression. Those narrative sequences that involved only Pekar in the panel held some of Crumb’s best moments. With a simple hand gesture or shrug, he could imply indifference; a scratch of the chest was a personality quirk; slumped shoulders a sign of resignation. A smile, a downward tilt of the head, a run on the head, wild expressive eyes, hands in pockets, a moment of silence. By using a quick alteration of form and expression, Crumb could move the narration along with great dramatic fluidity while still maintaining a stylized visual and, most importantly, express great emotions.

Line Quality

Crumb has a unique style that was sensational when he first hit the underground comics scene in the 1960’s. Known for his gritty realism set against cartoonish characters inspired by comics from the 1920’s and 30’s, his style evolved throughout his collaborative relationship with Pekar from the heavily hatched short line work of the 1970’s through a slightly more clean period in the mid to late 1980’s. Crumbs most iconic style is his 70’s grit that reflected Pekar’s skewed vision of the American dream in the midst of the Postmodern revolution.

Indeed, Crumb’s style at the time resembled a deconstructed old time cartoon which had been reassembled with short dashes of lines and crosshatch blocks of shadow. With his combination of visual candour and the less attractive elements of the human condition, it could be argued that out of any collaborator that Pekar worked with, Crumb was best suited for his material. When comedy was required, Crumb delivered. When a heavier touch made more sense, Crumb could manage that too. Their mutual experiences as underground creatives and all the struggles associated with that way of life could be credited with the high level of synergy that the Pekar/Crumb relationship produced.

Summation

Crumb and Pekar evolved out of the same mould, that of the self made man within a heavily institutionalized comic industry. Pekar’s wish to tell personal stories of what real life was like living in America and Crumb’s unsympathetic style meshed perfectly together. It is hard to imagine Pekar’s prose being set in traditional comic hero style after seeing Crumb’s intensely personal interpretation of the text with all it’s nuance and variance.

By Brian Bork

Greg Budgett & Gary Dumm

Graphic Style

The combination team of Greg Budgett and Gary Dumm span the breadth of “The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar”, showing their long collaborative history with the author. They would often work on the same story for Pekar with one doing the pencil work and the other inking. Dumm also worked by himself were he did both pencils and inks for the whole “strip”. While they share a similar style and narrative approach, they did differ in some ways as well.

Budgett as Penciler – Not Quite Superhero

Budgett’s style is perhaps the closest to mainstream comic art of the 1960’s and 70’s with its strong graphic forms and emphasis on narrative flow. He liked to place Pekar and his other characters into strong, well delineated environments with a near technical sense of perspective. Often times, the level of detail in the foregrounds equaled the same level of detail in the backgrounds which could create a conflict of visual hierarchy but the way he organized his frames did not cause any compositional problems.

His storytelling through compositional arrangements is what makes Budgett’s style successful. The flow from one panel to the next is natural, the placement and configuration of his point of views benefited the conversations between characters or Pekar and his environment. He was more found of narrative sequences as opposed to the confessional approach of breaking the fourth wall like Crumb. He used it sparingly.

While he excelled on the technical side of illustration, his capacity to have his characters express a broad range of emotions was limited. This was left to Pekar’s prose which manage the job just fine.

Dumm as Penciler – A Place Between

Dumm as Penciler could firmly be placed between Crumb’s grittiness and Budgett’s graphic delineation’s. He had some issues with rendering anatomy cleanly, especially when a character would be leaning forward or bent in an awkward way.

Like Budgett, Dumm also enjoyed the narrative approach when setting Pekar’s words to panel. He did break the fourth wall like Crumb but as with Budgett, he enjoyed telling the story more with images then relying more heavily on the words. He had a great sense of creating relationships between the characters in the frames. They sit beside each other, stand around a kitchen table and talk casually, glance over each others shoulders and so forth. These types of everyday interactions and how they are illustrated by Dumm fit Pekar’s writing style nicely and add to the wonder of everyday existence that Pekar so loved to document.

Summation

Wether they worked together or separately, Budgett and Dumm shared similar traits but had their own unique take on how to construct a good graphic narrative. Budgett’s clean graphic style offered a skewed take on something close the the superhero style of the times while Dumm’s less clean world but thoughtful compositions added to the narrative flow of Pekar’s stories.

Brian Bork

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Gerry Shamray

Official website.

Gerry Shamray began working with Pekar as an art student after he came across the fellow Clevelander’s Splendor in the “underground” section of his local comic shop. He collaborated directly with Pekar by taking pictures of him, his environment and the streets of Cleveland as references. This, in combination with his stroke sensitive style maintained the realism of earlier artists in the series but added a sense of naturalism in his environments and character drawings which transcended shape and form during Pekar’s more introspective writings.

Awash in Light and Dark

Shamray’s unique style within the Spelndor canon is important because it marks a merging of trends in one instance and a movement away from the stylistic heaviness of the 70’s. While his style showed the same level of realism as Crumb, Dumm and Budgett, he furthered the enterprise with the beauty of naturalism.

A particularly effective story is Pekar’s reflections on his life two years after his second divorce. He’s wandering through a park that’s been shut down for “restoration” and is contemplating his past and present circumstances. Shamray illustrates the whole excursion with graphic blocks of light and dark, detailed with more sensitive internal lines. His line quality is comparable to a squiggle or continuos contour that compresses to form shadow and extends to describe form. He even manages some tonal variation within his shadow blocks by doing a loose squiggle that suggests reflected light.

The park itself and all its natural beauty is handled with great care so that one can feel the texture of the bark on a tree or the dried out autumn leaves strewn across the grass. The intensity of light and dark within the landscape and on Pekar should be harsh to the eyes, but the delicacy of the line work upon closer inspection lends it a delicacy that one does not expect.

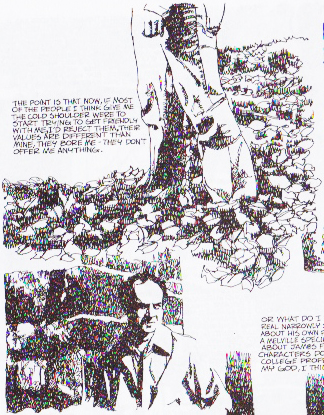

Introspection and Dissolution

Pekar becomes absorbed in his own thoughts quite often during the Splendor series. The way his artists illustrate these personal, inward moments often shows the problem solving energies of their style as the narrative flow does not involve situations with other people or places. Shamray’s use of the park and nature as a means to enclose Pekar into an introspective state fits comfortable into humanities role for nature as mediator between the mind and soul. It becomes a meditative place where barriers are broken down and we experience the mingling of our thoughts and feelings. This dissolution of forms is portrayed effectively by Shamray because he abandones traditional comic book “frames” and simply creates areas of space on the page with its size his only boundary.

Shamray’s style may be most suited to Pekar’s introspective moments compared to his other artists because Sharay likes to break down form and structure into blocks of tonality where they are free to merge with the each other. Form seems to dissolve in and out of being in Shamray’s Splendor so that the eye ends up completing the picture.

Summation

Realism and Naturalism are an effortless part of Shamray’s style, but the way in which these two traditions shift and transcend into something metaphysical goes beyond their respective genres. In an almost gestalt-like approach, Shamray’s broad areas of light and dark are broken up by tightly wound, agitated lines that inform only portions of the positive space while the remainder merge with the negative regions. Such merging of darkness and light contrasted against broad graphic blocks of tone show the boldness and subtlety visually that Pekar instills in his writings as well.

Brian Bork

_________________________________________________________________________________

Susan Cavey

An interesting counter point to Shamray is artist Susan Cavey. While Shamray used line to show the contrasting power of solid shapes dissolving within or at the edges with line work, Cavey used points. Her style is a simple blend of point mixed with some contour, flat shapes and the odd hatching. Out of any of Pekar’s contributors, Cavey’s style was the most abstract and least representational.

Transitory Tone

Cavey’s style emphasized shape and from through the interplay of tonal shading, but not necessarily from a source of atmospheric or artificial light. Her compositional language was intentionally designed so that she could bend the rules of tone to fit the needs of her panels. One of the more interesting examples of this is during the story of Sally when Pekar’s character is waiting for a lift from her but she takes to long so he walks home in the rain. Halfway there, she drove up behind him and picked him up. Cavey used a light/dark, negative/positive transition within the same frame to show the change in Pekar’s mood. The first half of the frame is Pekar walking in the gloomy rain, the sky and ground showing dark while the car and his figure are in light. The other side of the frame, as he opened the door to get in, reversed the tone contrast so that his figure and the car show tone while the sky and ground became tranquil and pacified (representing his change in mood).

Her mix of stippling, hatching, contour and solid blocks gave her art a dissonance that also helped emphasis the discordance in Pekar’s narrative. During moments of anxiety and great feeling, her combination of line work punched up the emotional expression, or flattened it out when only stippling was used. This approach was used nicely during the court scene of Pekar’s “Jury Duty” story to give the proceedings some extra kick. The jury selection process is filled with rough outlines, heavy tone shapes and angry hatching contrasted against the shifty nature of the prosecutor whispering into the judges ear in all its soft stippling and weak outlines.

The Symbol as Narrative

Cavey’s unique approach to American Splendor showed an interest in the potency of symbols and icons to accentuate the narrative beginning with Pekar himself. For Susan, Pekar’s most distinguishing feature was his curly, out of control eyebrows. The furry entities coil and writhed out into loops at the edges which also helped to accentuate his eyes, another point of focus for Cavey.

She also captured the symbolic postures of human body language as a means to convey successful narrative. Rather then fully fleshing out a leaning figure with detail, she simply stippled the negative shape around him to suggest the outline of his pose. In this instance, a liberal defence attorney leans casually against a table with the accentuation of his legs and hips being defined by a heavy line on one side and dense stippling in between. There is little contour within his lower half, only the outward negative shapes. Thus we are left with more of an impression or reduction of the pose into symbolic representations of confidence and composure.

In the same pannel story where Pekar is called for jury duty, Cavey recalled the political symbols that the author is talking about in both literal and iconic terms. Nixon becomes both a true representation of corruption and a symbolic one when he’s illustrated with his classic parting V hand signs. The stars and strips with a war plane also make an appearance in the same illustration with other disreputable politicians to further the point. Cavey wasn’t afraid to add a clock directly in the background with nothing else but foreground figures is she felt that it’s importance as a symbol for time was needed or the superimposition of a phone between frames to implicate it’s interruptive narrative importance. Cavey used symbolic language in a subtle, yet instructive way to tell the story.

Summary

Cavey was one of the more unique contributors to American Splendor in that her style was non conventional. The impression or idea is what mattered to her when compared to traditional representation. She liked to capture important ideas or characteristics through the use of visual symbols which helped narrate the piece in a more literal manner. Her aesthetic style of contrasting both light and dark, positive and negative space, and line/point quality helped delineate what was a key item or person within each scene.

Brian Bork

______________________________________________________________________________________

“Words and Pictures, they could be more of an art form”- American Splendor (2003 film)

THE ART OF AMERICAN SPLENDOR

Allen Ribo

The story of American Splendor is a constantly-evolving art form. From the moment Harvey makes his first comic to the collaboration with cartoonist Robert Crumb (and future artists), Splendor quietly surpasses the medium in the form of honest, slice-of-life storytelling. By quiet, it didn’t aim to make the comic industry take notice. The last time outside genres surpassed the superhero genre it was trumped by a notorious lawsuit, effectively eliminating ‘the competition’ (Frederic Wertham lawsuit AKA seduction of the innocent).

The first issue, “Big Bicentennial Issue” covered a variety of themes, including race, romance, humor, and sexuality in 70s America. Splendor was incomparable to many of the comics on the newsstands. At this time, mainstream comics focused on realism in the art and juxtaposed characters occasionally to serious subject matter. It could be coincidence that Splendor influenced on the use of the ‘real world’ as a lens to filter stories to. The closest to reality as comics got was in the narrative Stan Lee wrote for many of the Marvel characters. Harvey wrote these stories, as if he was using material from an interview, then through the ‘magic’ of the comic medium (and collaborators Robert Crumb, Gary Dumm and Greg Budgett) create a slice-of-life story. The artwork in the first issue was crude, abstract, and slightly cartoon-like. The men often looked average; sometimes they were skinny, and sometimes they were fat. His portrayal of women were hardly skinny, they were often voluptuous. There was a sexual undertone in the way they were drawn; Harvey would make up for the tone with his honest narrative.

Harvey would go on to work with numerous illustration and cartoonist collaborators. At the same time, the stories went from a fictional narrative to the life of Pekar as a focal point of the story. The ninth issue, released in 1984 focused on Pekar’s life from his friendship with Toby, his interactions at his workplace as well as an interesting story that addressed his feelings to Comics becoming a speculative market. At this point, the artwork takes a departure from its cartoonist aesthetic in favor of realism, notably the work of Gary Shamry. The realism is backed up by a serious narrative. This issue is important in a closing line that would resonate to any artist, writer or working in a creative field: “Will anyone at all read my stuff after I’m dead? Will they wonder what kind of guy I was?”()

In the early 2000s, after the release of the film adaptation, new stories were published under Vertigo, a mature imprint of DC Comics. Dean Haspiel and Ty Templeton joined the ranks of main collaborators Crumb, Dumm and Budgett. Instead of the fledgling life and ordeals Pekar often portrayed, it shifted to a slightly comedic tone, dealing with themes as fatherhood, identity and family. The stories mostly told of his family life (with wife Joyce and daughter Danielle), his identity as an American Jew, and the changing world as he reached seniority. Unlike the early issues of Splendor, these issues had a more pop-comic aesthetic. This is mostly due to his artistic collaborators.

The art of American Splendor is a constant metamorphosis; it is unique to the comic medium for its honest dialogue, the variety of art styles, and how it endured the test of time. Pekar is not Superman, nor is he Batman. Thanks to Pekar, the careers of his collaborators birthed; Robert Crumb continues to create his own books including his unique interpretation on the Book of Genesis.

___________________________________________________________

THE CRUMBS OF SPLENDOR (by Bushra Mahmood)

“Harvey is often frustrated by the artists lack of ability to break out of the standard heroic comic book style of portraying characters.” – R. Crumb

Right of the bat it is evident that Harvey Pekar chooses his art based on it’s crudeness and uniqueness rather than it’s marketability. His artists do not embrace any classical aesthetic

When Harvey Pekar chooses an artist, his criteria is not what most would be drawn towards, He does not pick the masters of their craft, the ones who render with great precision or define the light in an ethereal matter. He chooses the artists who push away the traditions of illustration and bring in a crude and unique perspective. His illustrators do not draw each line with mathematical precision or a classical composition; their lines are aggressive, overlapping, angry and alive.

In choosing such an aesthetic for his comic it becomes evident that he wants his message to take the front seat. Harvey wants his book to be read properly with each sentence understood rather than overshadowed by the art.

Harvey embraces the ugly in his life and allows the illustrator to create that in whatever they feel is appropriate.

Crumb is one of the first characters that we are introduced to in his book, The fact that he himself is illustrating his portrayal makes the story a lot more interesting. We see him as a shy and nerdy guy who transforms over time through his fame, through the story line and in the way he is illustrated. At first glance Crumb draws himself in an extremely unattractive and standoffish manner, this is surprising because one can assume that when portraying themselves they could be forgiving, however this crude honesty can explain why the book is so successful. He draws the way Harvey see’s things, and Harvey sees them the way that they truly are.

For example when he portrays his friends Freddy, he chooses the work of Crumb. This is because we find that Freddy himself is a very unreliable friend who constantly uses Harvey; at the same time, being a friend Harvey can not make Freddy out to be a villain or a negative character. In order to portray Freddy in the most appropriate manner, he uses a satirical portrayal through the art of Crumb.

The reader feels at ease and understands that Freddy is a person of flaws instead of a villain. This distinction is why a graphic novel is a much more effective method of portraying Harvey’s stories than a book alone.

Crumb starts and ends the book with his illustration thus playing a pivotal point in the books aesthetic. Mr. Boat is another interesting character that pops up throughout the book that is almost exclusively drawn by Crumb; He is a bitter older gentleman who constantly criticizes Harvey in his taste in music, books, women and business practices. However even through the criticism, the book ends in him wishing Harvey good health, so the character takes on a mentor role. It’s interesting to note that there are no real villains in his book, because in reality, there are no extreme villains in real life. I also assume that Harvey does not intend to make anyone a villain after publishing the books hence he always gives them some humanity and a quality the reader can like.

Crumb was recently honoured for his unique perspective when he decided to recreate The Book of Genesis, this was met with such acclaim that he made the Best Seller List in 2009

By Bushra Mahmood

Hi Brian,

In reply to your post on Gerry Shamray:

I think you did a great job analyzing Shamray’s drawing style. I agree with your comment that is work is well suited for Pekar’s introspective moments because of his breakdown of form and structure in favour of a free, natural composition.

In the article you linked to, Jerry states: “Harvey was a one-of-a-kind individual. He embraced the ordinary and made it extraordinary with his brilliant, insightful stories about day-to-day life. I have no doubt that people will be reading and learning from his clever observations on the daily grind for many decades, if not centuries…It was a true joy for me to work with him…It is Harvey who is the real artist, who through his vision, always inspired those around him, especially me.” While reading this I could almost feel Shamray’s absolute wonder for Harvey and his writing. The first three sentences of that quote especially, I think give an insight into how Shamray wanted to illustrate Harvey’s stories because he held Harvey and his work so highly: showing insight and making the ordinary extraordinary through his use of realism and naturalism and as you said, “the way in which these two traditions shift and transcend into something metaphysical.”

This is a link to another illustration by Gerry that I think shows again his use of positive and negative value in an almost ambiguous way, though with much more form, structure and stylization. It is also similar in that the eye must complete the picture, because this illustration is so highly contrasted, the viewer is left to wonder about the details.

-Victoria

RE: The Crumbs of Splendor

Hey Bushra,

I completely agree with the idea that Pekar didn’t want to portray extreme villainy in his works but rather the perception of one person’s view of another. Even Pekar himself has his undesirable moments like when he bullies Crumb into drawing his comic with the artists as cowering victim. The fun component of that story was that Crumb himself drew the frames and got his “revenge” by showing Pekar as a loud and pushy lout.

I personally think that out of any artist Pekar worked with for American Splendor, Crumb’s style matched his prose the best. One can usually tell when an artistic venture works brilliantly due the natural feeling of synchronization as one absorbs the work. The Pekar/Crumb collaboration works wonders in that respect.

Brian.

Hey Brian,

I understand what you mean when you talk about the unsympathetic style of Crumb, I think it’s crucial in his identity and notoriety as an illustrator. Without a combination of crudeness and comedy I think it can be very difficult to understand where he is coming from. The fact that his illustrations posses a certain novelty allows the reader to take a less serious tone to his work and analyze it in a less offended manner. You might be interested to read that Robert Crumb made the news recently for a rejected cover commissioned by The New York Times

You can Read more of the Article here

– Bushra Mahmood

I think out of all of the illustrators, Gerry Shamray probably stands out the most to me, As an Illustrator I felt a sort of detachment from his work, not from his technique, but his composition. When you stated that he directly used photo reference it became a lot clearer why I sensed something different. I acknowledge the degree of skill that’s involved in Shamray’s work, however I felt the work was a little removed from everyone else’s interpretation. This is the case where a technical analysis was a good choice rather than talking about the personal interpretation.

Denis Peterson is an illustrator who does phenomenal hyperrealism, The work is undeniably meticulous and precise, However there is something unsettling about how perfect it is. This brings up an important debate about the merits of copying a picture as opposed to using references and inspiration.

-Bushra Mahmood

Hi Bushra,

In one of the comics in American Splendor, Harvey says he prides himself on being an individual. I think his need for individuality is part of what drew his attention to illustrators who as you said, “Push away the traditions of illustration and bring in a crude and unique perspective.” I stated in my response to your post on music that Harvey’s personality and character are reflected in American Splendor and I think the art is another example of this because he is a “crude and unique” individual. I also liked your comment on embracing the ugly, as I think that is exactly what American Splendor is about.

This link is an organized list of all the artists Pekar collaborated with while writing the American Splendor comic books.

-Victoria

Hi Brian,

I read your entry on the work of Robert Crumb and I appreciated your articulation to his expressive aesthetic. If his work were compared to the modern indie comics’ creators, he would find much difficulty standing out. That said, the era in which American Splendor was released makes his collaboration with Harvey Pekar important. American Splendor brought about a change in the comics medium inspiring a ‘do-it-yourself’ motif in creating comics.

As for the team of Greg Budgett and Gary Dumm, I was impressed by the evolution they made as artists throughout the history of the comic. Their metamorphosis from simplistic, cartoonist style to a slightly realistic tone left an impression on me as a comic reader. It is rare to see most comic artists in the medium evolve with time due to the demands of production time and deadlines. Few artists strive to push themselves to stay relevant in their own field. In observing the maturation of Budgett and Dumm and their work, it changed my perspective on the creative fear of “living under a rock”. It stresses on an idea that any great artist will embrace their failures and see it as a way to continue producing artwork and improve rather than failure as a form of resistance.

To conclude my entry, here is a video I found on Milton Glaser and the Fear of Failure: http://vimeo.com/23285699

Hi Brian,

Interesting observations on my art.

I really respected Harvey’s work and wanted to bring out the best out of his stories. The story you refer to had Harvey entirely in self-thought from first panel to last. I felt it was important to throw away the panel borders as they signify (at least to me) awareness of a given moment. When in deep thought mood most folks are not paying attention to their surroundings but are locked into an internal debate and analysis of their life. I wanted to blur the “panels” even more but was afraid it would prove too intimidating to readers.

As for the use of photos, Harvey told me he saw himself as a human tape recorder so i felt the best approach to this style of writing was to be the camera. I also saw his stories as mini-movies. I didn’t see myself as an artist (a word I take seriously and know that I am not worthy of) but more like a filmmaker when interpreting his work.

I miss not having Harvey around in Cleveland. He was a true artist and a really interesting guy. It’s wonderful to see his work appreciated.

Sincerely,

Gerry Shamray

Hi Bushra,

I read your analysis on the art of American Splendor and your observation of the work of both Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb. What I found to be interesting was in pointing out the artistic choices of Pekar; in most comic collaborations, a writer will favor an artist who demonstrates a master proficiency in their work. The pioneers of comics were working cartoonists and writers dressed in suits, rolling up their sleeves ready to work on a deadline for a comic. In the case of Splendor, it does not look to a polished finish, but an interesting kind of grime. To see the evolution of Robert Crumb from having a humble start in his collaboration with Harvey Pekar to being one of the most renowned cartoonists in comics is nothing short of amazing. It would be interesting that the famous visual half of Splendor would end up doing long, ambitious projects including his own interpretation on the book of Genesis.

As for Harvey Pekar, he is a true collaborator of comics; he will give his artists room to interpret his scripts without being tied to his demands or wishes. This is evidenced in his frequent collaborations with Crumb, Dumm, and Budgett. When the collaboration is good and there is as much give-and-take, the result is nearly a twenty year story that embodies the work of mostly four men.

To conclude, here is a video that introduces Pekar and Crumb, voiced by Dan Castellaneta of Simpsons fame, titled “American Splendor: The Harvey Pekar Name Story”.